- Home

- Mark Paul Jacobs

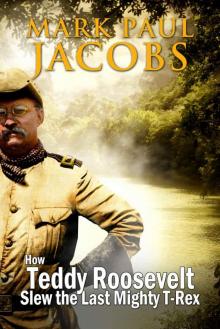

How Teddy Roosevelt Slew the Last Mighty T-Rex

How Teddy Roosevelt Slew the Last Mighty T-Rex Read online

How

Teddy Roosevelt

Slew

The Last Mighty T-Rex

A novel by

Mark Paul Jacobs

Copyright © 2013 by Mark Paul Jacobs

All rights reserved

Cover design by AM Design Studios

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Cover Design by AM Design Studios: You can find their website by clicking here: AM Design Studios

Author’s note: I hope you enjoy this adventure story as much as I enjoyed writing it for you. Please don’t be afraid to tell me what you think via reviews or my Facebook page. I’m eager to hear from you.

Discover other titles by Mark Paul Jacobs at:

Mark Paul Jacobs Smashwords Profile

Visit my writer’s blog at:

Mark Paul Jacobs Writers blog

Visit Mark Paul Jacobs's Facebook page:

Mark Paul Jacobs Facebook page

Join Mark Paul Jacobs on twitter:

Twitter MarkPaulJacobs

Table of Contents: How Teddy Roosevelt Slew The Last Mighty T-Rex

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 1

José Bonifácio Telegraph Station

Mato Grosso, República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil

February 22, 1914

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt—former President of the United States of America, living legend and enigmatic leader, world-renowned for rallying his Rough Riders up San Juan Hill—had long surrendered any notion of growing accustomed to the relentless Amazonian rains. Bone-weary and exhausted after a grueling seven week slog up and across the muddy Brazilian divide, Roosevelt tossed uncomfortably atop a threadbare cot and listened to the incessant rush of falling rainwater against the thatched roof of his daub-and-wattle hut. Even the downpours he and his second-born son, Kermit, had so frequently endured while wandering the African savannahs just four short years before, seemed subdued compared to the saturating deluges that tumbled routinely from the bleak skies over the Brazilian highlands. And this dreary night would prove no exception, he fittingly concluded.

Roosevelt swatted an invading sand flea and casually brushed aside some other nocturnal creepy-crawlies. He pulled his body inward and stared out of the open doorway and into the sopping wilderness. Teddy Roosevelt’s typically unfaltering mind swirled with countless troubling thoughts.

The rains were an eternal annoyance and certainly an impediment to the expedition’s progress, he mused, but the humidity that smothered these lands was constant and nearly unbearable. The permeating heat, combined with Teddy’s lifetime struggle with asthma, often felt like a prizefighter’s right-handed roundhouse to his fifty-four-year-old gut. And to make matters worse—and verified by personal accounts offered by the experienced Brazilian officers—his misery would only worsen as they descended into the heart of the Amazon’s sweltering jungle. Theodore Roosevelt possessed a keen sense of own body’s steady decline with his advancing age, and he inwardly bemoaned the lessening of his usual copious vitality. If only I could recapture just a sliver of youth, he pondered. If only I could gather enough strength to reclaim some of my former vigor, before all is lost on this most inhospitable continent.

Yet most worrisome of all was the crushing reality that the most daunting part of the journey remained ahead of him. Mapping the last unexplored waterway of the Amazon basin would be without question Roosevelt’s greatest challenge, and the headwaters of the Dúvida River—the so-called “River of Doubt”—snaked peacefully northward just a few day’s journey away. Merely a decade after being mangled in a trolley accident, having his retina torn while boxing in the White House, and less than two years following an assassination attempt that left a bullet permanently buried in his chest, Theodore Roosevelt marked each grueling day fighting what he derisively called, “The withering fortitude of lesser men.”

Yet Roosevelt himself remained hopelessly human, and the dark minions of doubt did occasionally attempt to invade his normally stalwart psyche. But unlike ordinary men, Roosevelt learned at an early age to conjure up barriers to restrain his most destructive proclivities. He simply took a deep breath and stirred himself to anger—it was not his nature to let any physical task stand in the way of his stated goals, regardless how demanding or seemingly impossible. He owed it to his beloved Kermit, his wife Edith, the men of his expedition, and finally to the American Museum of Natural History. He had to remain unwaveringly resolute.

Roosevelt rolled over and peered at his snoring twenty-four-year-old son, cloaked within the hut’s darkness. Beside Kermit’s cot and under a dying candle, Teddy could discern an open book, a parcel of paper and a pen, and a dog-eared photograph, presumably of Kermit’s fiancée, the lovely Belle. Having his son on this expedition was one of several factors sustaining Roosevelt’s hope and buoying his spirit. Yet another was the inclusion of the expedition’s co-commander, the legendary Brazilian military officer and explorer Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon. Theodore Roosevelt sustained a strong feeling of unflappable confidence in Colonel Rondon from the very first moments they met upon disembarking the side-wheel steamship Nyoac after it had settled upon the docks of the Paraguay River’s upper reaches. Rondon had personally directed the carving of Brazil’s newly commissioned telegraph lines through this brutal wilderness, a wondrous and heroic task of which Roosevelt never tired of hearing tales on the trail or by the nightly campfires. In fact, they had followed the fearless Brazilian commander’s blazed pathway across the Mato Grosso plateau, and his strategically placed telegraph stations became welcome respites during their plodding overland journey.

But having Kermit by his side through this ordeal is what really warmed Roosevelt’s heart. Kermit had been working in South America for over a year, and the ever-adventurous Teddy beamed proud knowing that his own son had chosen to strike out on his own by carving railroads and building bridges upon one of the most mysterious continents on earth. His only regret was diverting the young man from his new career and keeping his son separated from his first true love. Smiling inwardly, Roosevelt suspected from the start that his wife had conspired to ensure Kermit’s presence

on the expedition. Edith’s worries were plainly evident during the months leading to Teddy’s departure. The old, broken-down goat would have to be looked after, Roosevelt thought, with a mocking and indignant grin. And yet Roosevelt pondered another twisted aspect of he and Kermit’s relationship, formed in part by closely observing his son’s actions during their recent African adventure. Although encouraged by Kermit’s tireless work habits and bravery, Kermit’s recklessness often gave his father great pause, giving rise to the obvious question: “Who would ultimately be responsible for looking after whom?”

Kermit’s snoring suddenly ceased, and the younger Roosevelt rolled and released a deep and repeated cough. With a moment’s pause and an incoherent grunt, Kermit flopped again and resumed his cadenced snore.

Theodore Roosevelt’s eyes narrowed with concern. Kermit had been afflicted by recurring bouts of malaria since childhood and malarial diseases were one of the expeditions’ paramount concerns. Roosevelt felt fortunate to have a doctor like Jose Cajazeira along on their journey. The intrepid medic administered doses of quinine on a regular basis attempting to restrain the diseases’ onslaught. But even Colonel Roosevelt himself was not immune to the scourge of the equatorial jungles, and recently he was beginning to notice flashes of fever during the overland trip, an inconvenient hindrance that he kept, at least for the present, to himself and Dr. Cajazeria.

Roosevelt tried to settle himself comfortably upon his bug-infested cot. His eyes opened slowly, gathering in the shadowy doorway—the crude wooden frame dripped rainwater rhythmically to the muddy ground below. The sounds of the Brazilian wilderness echoed in his ears and danced through his head.

There was a dark foreboding that weighed on Roosevelt’s mind as the expedition moved deeper into the unknown and farther from modern Brazil’s more established settlements and flourishing cities. And this feeling most assuredly was shared by the rest of the intrepid troupe, especially his fellow naturalists, George Cherrie and Leo Miller. These lands were hardly unoccupied when Rondon slashed his way through this wilderness, bringing with him a measure of contemporary technology and disrupting the native’s nearly Neolithic lifestyles. The Pareci Indians were a harmonious lot, whom Rondon quickly made peace. The Pareci even drew salaries helping to protect Rondon’s telegraph station at the village of Utiarity. But the Roosevelt-Rondon Expedition was now intruding deep into the lands of the naked and warlike Nhambiquaras, one of the most primitive tribes of the Amazon, and Roosevelt had deep reservations.

Colonel Rondon had made first contact with the Nhambiquaras just six years previously, and the natives appeared impervious to Rondon’s overtures of a solid and lasting peace. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers, settling down only for the rainy season, and their tribes were scattered into independent bands making Rondon’s task nearly impossible. But as testament to Rondon’s perseverance—and through the issuance of many lavish gifts, Roosevelt noted—the Nhambiquaras gradually succumbed to Rondon’s big-heartedness. And eventually, through the passage of time, they settled into a trusted relationship with the intrepid Brazilian Colonel and fashioned an uncomfortable peace with his telegraph workers. Although friendly to Rondon personally, the Nhambiquaras’ unease with outsiders was palpable—even the slightest provocation could turn badly and even the simplest misunderstanding could be deadly to Roosevelt and his expedition.

And as Rondon recently and ominously warned, the lands surrounding the River of Doubt would be, quite probably, inhabited by Nhambiquaras or other native groups unknown even to Rondon himself. These Indians would regard them only as invaders, an unsettling thought to Roosevelt, who always remembered the first law of wilderness survival whilst trespassing upon occupied lands: “Friends proclaim their presence; a silent advance marks a foe.”

Theodore Roosevelt’s battered body finally succumbed to weariness as the dim shadows flickered upon the highland’s gentle breeze. He harkened back to feelings of powerlessness, of a dark stalking force that he could, and yet he could not, quite comprehend. Roosevelt was beginning to notice that Rondon’s “friendly” Nhambiquaras were becoming increasingly bolder with himself and his men as each day passed. The natives danced, smiled, and joked before their visitors, and they even accepted Rondon’s gifts as a gesture of goodwill. And yet there was an underlying tension, a palpable sense of infringement, a feeling that the expedition was encroaching upon these people’s lands and threatening the basic underpinnings of their simplistic and ancient culture.

Teddy sensed an ever-present monster stalking the expedition, a most dangerous and deadly predator with many probing eyes, capable of wiping all trace of the expedition from the forest in a flash of an eye, if they suddenly and arbitrarily chose to do so. But, unlike any other predator or foe Roosevelt had faced in the wilds of Africa or across the lines of battle, this potential adversary hid in plain sight.

Theodore realized that the greatest threat to the expedition was not drowning or starvation, or even by the claws of a jungle animal, or a deadly biting fish. Staring out into the wilderness, Roosevelt’s stomach soured knowing that their greatest menace was explicitly obvious and also inherently human.

CHAPTER 2

Roosevelt woke early, greeting the new day in much the same way as he did every morning since leaving the relative comforts of the steamship Nyoac and beginning the overland journey. He stretched some kinks in his neck and back, took a deep breath, and then strolled to the encampment’s edge for his morning constitutional. Returning gratified and reinvigorated, he ritualistically shielded his head with netting before sitting down and documenting the previous day’s events.

Despite the early hour, Roosevelt noticed the expedition’s makeshift camp already stirring with hushed Portuguese chatter and restless pack animals. Colonel Rondon’s assembly of rough-and-tumble camaradas—the expedition’s laborers, porters, and future paddlers—lined up with military precision against the backdrop of the isolated Bonifácio telegraph station. Roosevelt chuckled inwardly, watching the diminutive Rondon donned in camouflage Khakis pacing before his rugged men with his hands clasped behind his back and barking his daily orders like Alexander the Great leading his men against the Persian Empire at the Battle of the Granicus.

Cândido Rondon was the type of man Theodore Roosevelt could not help but admire. Barely five feet three, the Brazilian Colonel’s regal bearing and rugged forthrightness and adherence to strict discipline embodied just about every trait that Roosevelt himself advocated passionately his entire storied life. Rondon was already a national hero for his ventures across uncivilized Brazil, and it was he and his trusted Lieutenant Joao Lyra who, just a few years previously, had discovered and mapped the expedition’s targeted destination: the headwaters of the River of Doubt.

Roosevelt initially thought Rondon’s daily military ritual a bit overindulgent, especially for a civilian scientific expedition. Only later, and after getting just a small taste of the harshness of the Brazilian wilderness, did the former president fully comprehend the extreme nature of their mission. Colonel Rondon knew beforehand what Colonel Roosevelt could only have imagined before setting out on this adventure. Armed with the experience of leading men through these lands Rondon fully understood that conditions could deteriorate quickly, and the jungle could overwhelm and suffocate the unprepared with unmerciful ruthlessness. And it wasn’t long before the intuitive Roosevelt realized that strict discipline and ritual would bind these men together when all appeared hopeless—frankly, it would become their only chance at survival.

Rondon dismissed his camaradas to their daily tasks, and the men dispersed to feed and pack the stubborn mules and volatile oxen. Roosevelt finished up his notes and joined the naturalists Cherrie and Miller by the fire for a bold cup of boiled coffee and a rationed breakfast. The ever-dedicated doctor Cajazeira remained amongst the camaradas dispensing the men’s daily dose of quinine. “One can never take enough precautions against malaria,” Roosevelt would hear him preach often and repeatedly. “It wo

uld be foolish to miss even a single day’s ration while the life-saving drug is readily available.” Teddy Roosevelt quickly acquired a great deal of confidence in the expedition’s doctor, and it wasn’t long before the doctor’s sermons were ingrained into the expedition’s collective consciousness.

Kermit emerged from his hut and staggered to the fire. Roosevelt could not help but notice his son’s long and drawn face, which Teddy presumed was from a lack of restful sleep. Wordlessly, Kermit poured a cup of coffee and scooped a tin of steaming beans.

Theodore Roosevelt’s breakfast routine usually consisted of as much chit-chat as the taciturn Cherrie and the patient Miller could stomach. Kermit knew his gregarious father far too well and generally kept to himself, although he chucked gently on occasion, watching the expedition’s members weather the storm of incessant blather. Colonel Rondon, perhaps out of respect for Roosevelt’s military rank, offered the ex-president his most patient audience, and Roosevelt, true to his easygoing nature, always appreciated the gesture. Roosevelt often mused of his and Rondon’s nearly polar opposite personalities, and yet how fitting the co-commanders grew to understand each other so very well.

Rondon finished up relaying his final orders to his designated leader of the native camaradas—a strong and hard-nosed taskmaster named Paishon, a sergeant in Brazil’s Fifth Battalion of Engineers and a veteran of several of Rondon’s telegraph expeditions. The wiry Brazilian Colonel strolled to the fire and mixed himself a cup of herbal tea. Taking up a chair beside Roosevelt, he took a long sip. Roosevelt delighted in watching Rondon’s eyes glow following such a trifling indulgence.

How Teddy Roosevelt Slew the Last Mighty T-Rex

How Teddy Roosevelt Slew the Last Mighty T-Rex